On its 60th anniversary, Ross Perot’s Electronic Data Systems stirs loyalty and strong memories

Why do so many former employees say it’s the best job they ever had?

This story by Perot playwright and biographer Dave Lieber first appeared in The Dallas Morning News on Feb. 10, 2022. Featured image by Michael Hogue.

More than a decade ago, Melinda Lockhart of McKinney decided to start a Facebook group called EDS Alumni. The idea was to notify former employees of Ross Perot’s landmark company, Electronic Data Systems, of reunion events.

She came up with the idea when a few EDSers, as they call themselves, met for a meal at a local restaurant nicknamed IPC13. The company had a dozen IPCs – information processing centers. In an inside joke, IPC13 was the code name for the local restaurant hangout.

You could get into the Facebook group only by invitation. But even with that extra step, in its first week the group welcomed 12,000 former employees. Now it has 20,000 subscribers, and if you spend any time on it, you witness a level of loyalty to a now-shuttered American company that most modern companies could only dream of.

This year marks the 60th anniversary of the birth of Perot’s original computer services company in Dallas. As The Dallas Morning News reported on the 50th anniversary, “No homegrown company has done more to shape the business and civic landscape of North Texas than Electronic Data Systems. ... EDS invented an industry — building and running data processing systems for other companies and organizations — and formed the cornerstone of the Perot family fortune.”

It’s a family fortune that began with a $1,000 investment to start EDS in 1962. Today, according to Forbes, the family fortune is estimated at more than $7 billion.

Perot never used a computer, preferring his old Remington Rand typewriter when he needed it. But he kept up with the EDS Facebook group by having a screen installed in his office. Not a computer, just a screen tied permanently to the EDS Alumni group. He never posted anything, Lockhart says, but he enjoyed reading the comments from everyone.

Ross Perot wanted to read comments about his former employees at EDS on the Facebook alumni group. But Perot, who helped create the computer services industry, never used a computer. So he had a screen installed in his office to read EDS alumni postings on Facebook. Not a computer, just a screen.

Loyalty is everything

As companies today struggle to keep workers and build loyalty, EDS is a reminder of how corporations can turn themselves into families. It’s tough to do, but Perot pulled it off. Proof is the EDS Alumni page, where EDSers tell their favorite company stories for what many say was the best company they ever worked for.

When a top executive dies, they grieve together in their digital group. They love to post pictures of decades-old items with the company logo such as gold watches, golf balls, Christmas tree ornaments and coffee mugs with the slogan “People make all the difference.”

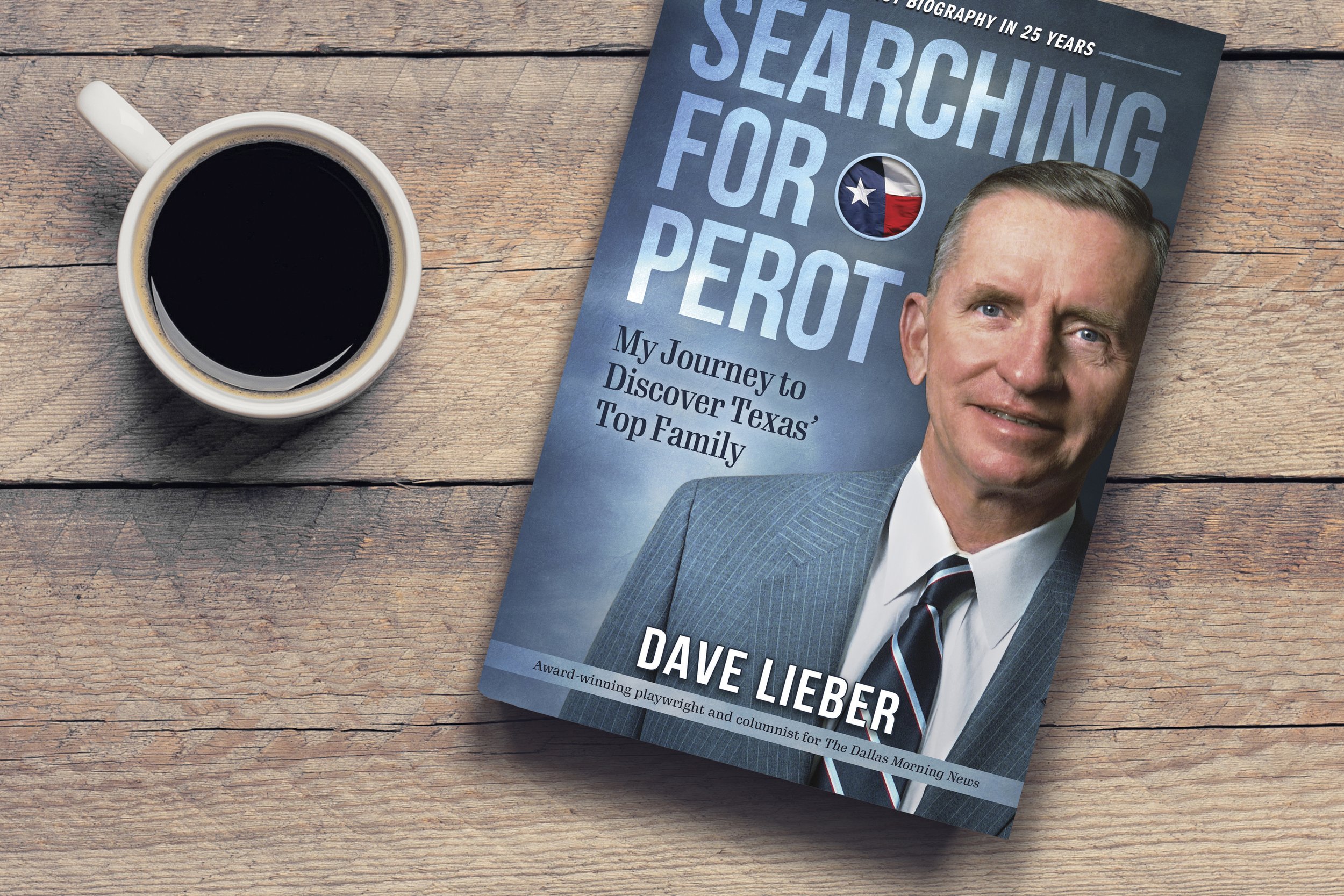

I studied the EDS culture for my new book, Searching for Perot: My Journey to Discover Texas’ Top Family, and for my play about Perot’s life, PEROT! American Patriot, which opens Feb. 11 for its world premiere at the Wheelice Wilson Jr. Theatre at the Coppell Arts Center. (Visit PerotBook.com).

Portrait by Michael Hogue

‘Hi, I’m Ross Perot’

As I studied highlights of his life, from growing up in Texarkana to his final days, the strength of EDSers’ affection for their boss and their company is, by modern standards, astounding. I’ve never seen thousands of people rave about a work experience that changed their lives with such passion and affection.

In person, when I give public talks on the new book and play, EDSers in the audience tell heart-warming stories.

Among my favorites is Perot’s avoidance of executive dining rooms in favor of the company cafeteria to foster personal connections. That’s where he met his employees, learned their names and their jobs and even met their visiting family members.

The place was run by a man in a chef’s hat. Meals were subsidized so employees only had to pay a few dollars.

Perot would try to greet everyone, usually saying: “Hi, I’m Ross Perot. I don’t think we’ve met yet.”

In this 1985 photo, Ross Perot shows off the company's newest information processing center in Auburn Hills, Michigan.(ASSOCIATED PRESS)

Taking a risk

It all came down to Perot, who had leadership abilities practically unheard of. He instilled it in his top executives — he called them eagles — emphasizing the heart of a leader is as important as the intellect.

As Perot liked to say, “Don’t focus on the sale. Don’t focus on what you are going to get or what the company is going to get. Focus on the problem that needs to be solved. If you can do that, the money will take care of itself. Let the money be the byproduct of what you do, not the goal. ... It’s that simple.”

Before EDS, Perot’s career at IBM selling million-dollar computers had stalled. The company wasn’t interested in his idea of creating software formatted for each individual client and teaching them to use it; IBM wanted to stick with hardware. Perot said if he stayed, he’d get stuck in middle management or be forced to take early retirement. But what to do?

Legend has it that he was in a Dallas barber shop waiting for a haircut. He was reading Reader’s Digest and came across a quote from Henry David Thoreau: “The mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation.”

“That’s me!” Perot thought. “I’ve got to try my idea, or I’ll never be able to live with myself.”

In church on Sunday a company name popped in his head, and he wrote it down on a pledge envelope: “Electronic Data Systems.”

The company started slow because it was difficult to explain what it would do. Perot explained: “We help companies make maximum use of their new computing power. And do whatever it takes to do that. If I have to move a cot into the data processing room and stay overnight, I do it.”

I found his first advertisement in The News seeking employees: “Immediate career openings in Dallas for men with 1 to 3 years’ experience with installed tape systems. Excellent compensation. Call ROSS PEROT, president, Electronic Data Systems.”

One of his first clients was Frito-Lay. Perot convinced its executives that his staff could do their data processing on rented machines. Frito-Lay canceled its IBM order for a new computer.

“I billed Frito-Lay $5,128 a month for data processing,” he once recalled. “I used odd numbers like 5,128 in those days to make it look like I knew exactly what I was doing and had figured everything down to the last penny.

“I tell my clients, ‘You have to pay in advance.’ And when they ask why, I say, ‘It’s customary in the computer services industry.’ But the business is so new, there are no customs yet. I’m making them up as I go along.’”

Perot favored executives who were former military, often returning from the Vietnam War. That gave EDS a military flavor. The men wore short haircuts. Beard and mustaches were banned. Dark suits and starched white shirts with a thin tie were required. Women wore dresses, not pants suits and definitely no miniskirts, which outside EDS walls was the custom of that era.

Why? Perot explained, “How much confidence would a bank or other client have in EDS if a representative of the company showed up in jeans and a mop of uncut hair?”

A fun workplace

Decades before tech companies like Google tried to create work environments that nurture employees with food and campus activities, Perot’s tech company did that. His first large corporate campus on the 7100 block of Forest Lane in North Dallas was the site of a former country club.

Perot kept most of the amenities. He cut the 18-hole golf course down to nine holes and hired a course superintendent to keep it in top shape. He also maintained a fishing pond, lighted tennis courts, jogging trails, a softball field, a swimming pool and a family picnic park.

The company grew quickly, mainly because EDS scored numerous Medicare and Medicaid contracts with various states. Perot fought so hard to win and keep contracts that EDS President Morton Meyerson (for whom Perot named the Dallas symphony center) once said, “Ross is a Boy Scout who knows how to street fight.”

EDS rules were not complicated: Never compromise the quality of work. Never compromise the company’s ethical standards. Never compromise how you treat one another.

For one workplace problem Perot was ahead of his time: sexual harassment.

On allegations against employees, he said: “I’m not going to compromise. This is the kind of place you’d want your daughter to have her first job. Two or three times a year I get a letter, and we pounce right on it. It’s handled by me personally. I’ve always said, ‘Anyone messes around with women in this place, I’ll kill ‘em.’”

If an employee got sick, Perot was known to charter an airplane and fly them to the best doctors in the nation. He made sure to visit them and their families to check that treatments were working.

Ross Perot stands in front of the second EDS headquarters, situated on Forrest Lane in North Dallas.(DMN Archives)

Stock goes public

When the company was 6 years old in 1968, EDS went public. Perot owned 10 million shares. The night before the Wall Street debut, Perot gathered his wife, Margot, and their children and, for maybe the first time, talked to them about money.

As Ross Perot Jr. once recalled: “Dad said, ‘Now tomorrow we’re going to take EDS public, and a lot of people are going to write about the money we have. But remember, none of this is important. The only thing that’s important is our family and how we take care and respect our family.’”

On that first day, a share of EDS stock was worth $23. Overnight, Perot made $230 million. When the stock climbed for $162 a share Perot entered the billionaires club. Fortune magazine called him “The Fastest, Richest Texan Ever.”

Electronic Data Systems Corporation's 1.5-million-square-foot corporate headquarters building, the EDS Centre, was in Plano, Texas, just north of Dallas.(AP)

Iranian rescue plot

In all the things he did before his death in 2019 — running for president (twice), trying to reform the American car industry, becoming one of the world’s great philanthropists — his most audacious act of all involved EDS.

In 1979, two of his top employees were held hostage by Iranian authorities. It was in the midst of the Iranian revolution, which prompted the Shah to flee and the ayatollah to fly in and assume power. Perot organized a corporate commando squad of 10 EDSers, all former military, led by retired Special Forces leader Bull Simons, to swoop into Iran and rescue the EDS hostages.

Against the best advice of his longtime lawyer, Tom Luce, Perot not only organized the raid, he also traveled to Iran and visited the employees in prison. His flying into Iran during the revolution was indicative of his commitment to rescue them. He wanted to personally assure the two executives that he was doing everything in his power to free them. Fortunately for him, he was not recognized by the Iranians.

Eventually, the men were freed, and the tale became a bestselling book by Ken Follett (On Wings of Eagles), and a TV miniseries.

In 1979 Ross Perot (left) masterminded a volunteer commando team consisting of Electronic Data Systems (EDS) ] employees. Their goal was to rescue two EDS executives held hostage in prison during the Iranian revolution. The two were rescued. They are Bill Gaylord (center) and Paul Chiapparone (right).(UPI)

When 52 Americans were taken hostage in Iran later that year and the U.S. couldn’t free them for more than a year, this made EDS’ corporate commando raid even more stunning.

EDS is no more. The company was acquired in 2009 by Hewlett-Packard Co., which then passed through a series of owners. And Ross Perot died in 2019. But the tales of this one storied company live on longer than expected. EDS shaped the corporate landscape because of the personality and creativity of one man who decided he didn’t want to live a life of quiet desperation.

Dave Lieber is “The Watchdog” columnist for The Morning News. His play about Ross Perot Sr. was performed nine times at the Coppell Arts Center, starting Feb. 11, 2022. For the companion book, visit PerotBook.com.